WATCH: How poetry brought Phoenix's queer community together

The group thems. started out as a weekend market and has since exploded by using poetry and other art to build up the community.

LOOKOUT identified local counselors and therapists in the state who practice new forms of conversion therapy despite an executive order that aimed to limit counselor’s resources.

Tres Adames believed he had to change himself.

It was 2010, and he had recently graduated with his Master of Divinity degree hoping to find a job as a pastor. Since childhood, he had been told that being gay wasn’t compatible with being a leader in the church, so he went to see a therapist who told him he could change his sexual orientation.

That therapist, John Hinson, is a licensed professional counselor in Arizona. Adames’ sessions with him deepened his shame over his sexuality and intensified his depression and anxiety.

This was not the first time Adames had sought out conversion therapy, and his experience with counselors, church leaders, and peers attempting to change his sexuality weighed on him: “The only time I’ve ever really been suicidal is when I was in these programs,” Adames said.

Hinson said in an email to LOOKOUT that he does not practice any kind of conversion therapy, but records show that he has been practicing it for years in the state, just under a different name. He is just one of several conversion therapists in Arizona, even though the practice has been labeled as harmful by the American Psychological Association and most other major mental health organizations. Last year, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs banned through an executive order any state agency from using resources to “promote, support, or enable” the practice for people under 18 years old.

But this is only a ban on state resources and hasn’t gone as far with other states forbidding the practice, entirely. According to the Trevor Project, an LGBTQ+ research and advocacy organization, there are at least 20 conversion therapists operating in Arizona.

Many of the therapists LOOKOUT identified reject the term conversion therapy, instead calling what they do “sexual attraction fluidity exploration” or “reintegrative therapy.” They say they are simply following the lead of their clients.

But when people like Adames seek out conversion therapists, the end-result has been real-world harm to clients: According to the APA, efforts made by mental health professionals to help change people’s sexual orientation increases the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts, especially in young people.

In a Trevor Project survey conducted in 2023 among queer people age 13 to 24, more than a quarter of those who had attempted suicide in the past year had been subjected to conversion therapy.

The American Counseling Association—the largest professional association of counselors in the country—says therapists practicing any form of conversion therapy violate a core ethical principle of modern medicine, the maxim to do no harm. And even though Arizona’s licensing board for counselors, the Board of Behavioral Health Examiners, uses the ACA’s ethics code as a baseline for determining ethical conduct, LOOKOUT has found that a number of licensed counselors in the state still offer conversion therapy, just using different terminology.

Contemporary conversion therapy has its roots in the work of Dr. Joseph Nicolosi Sr., known as the “father of conversion therapy.” Nicolosi believed that—with his help—gay people could renounce their same-sex attractions and live as heterosexual. He coined his therapeutic approach “reparative therapy,” and he believed that being gay was a trauma response that he could cure. His clinic opened in Los Angeles 1980.

In 1992, Nicolosi co-founded the leading organization advocating for conversion therapy, the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality, or NARTH.

Nicolosi also worked closely with leaders of the conservative Christian “ex-gay” ministry movement, which pushed supposed “success” stories of his therapies who had managed to renounce their attractions in the name of Jesus. The largest ex-gay umbrella ministry, Exodus International, had support groups for people like Adames who described themselves as struggling with their same-sex attraction. The group disbanded after 37 years in 2013, and issued a public apology to the people they gave services to.

Before seeing Hinson in 2010, Adames attended an Exodus International support group in college in Mississippi. The participants in Adames’ support group were mostly gay men. Taking a page from Nicolosi’s work, the leaders of the group would say that homosexual feelings were the result of unresolved trauma, specifically sexual abuse, Adames said.

Exodus wasn’t just one ministry—there have been hundreds, with member organizations in every state, including Arizona.

Exodus also kept a list of licensed conversion therapists to refer their members to, according to their website in 2012.

Hinson, Adames’ counselor, was one of those recommendations.

Adames said Hinson told him that getting more in touch with his own masculinity could help ease his attractions to other men.

“When you’re constantly told that you aren’t masculine simply because you’re gay, it can cause you to doubt yourself a lot,” Adames said.

Eventually, in 2012, with little progress made, Hinson recommended Adames go to a local conversion therapy camp called Journey into Manhood. Adames said Hinson had been a staffer for the camp and it was billed as a weekend for men who “feel that their homosexual desires do not reflect their true selves,” according to a letter he provided to LOOKOUT. It was run by the group Brothers on a Road Less Traveled (at the time called People Can Change). The organization was co-founded by David Matheson, an ex-gay protege of Nicolosi.

Journey Into Manhood continues to this day with upcoming events in Virginia, Indiana, Texas, as well as overseas in Israel, Mexico, and Egypt.

In 2010, when Adames was seeing Hinson, the Family Strategies Counseling Center in Mesa website described him as being “part of a staff of licensed therapists who specialize in sexual addiction recovery, reparative therapy, and other mental health issues.”

When asked by LOOKOUT if he ever practiced conversion therapy or reparative therapy, Hinson said he no longer uses those terms. "I respected the rights of clients and their decisions," he said. "This includes whatever choices they made concerning their behaviors and identity."

Hinson said he was phasing out of seeing clients entirely. He is currently listed as an Executive Team Member at the center.

After being contacted by LOOKOUT, Hinson’s staff page was edited to remove any mention of treating “same-sex attraction” as one of his specialties.

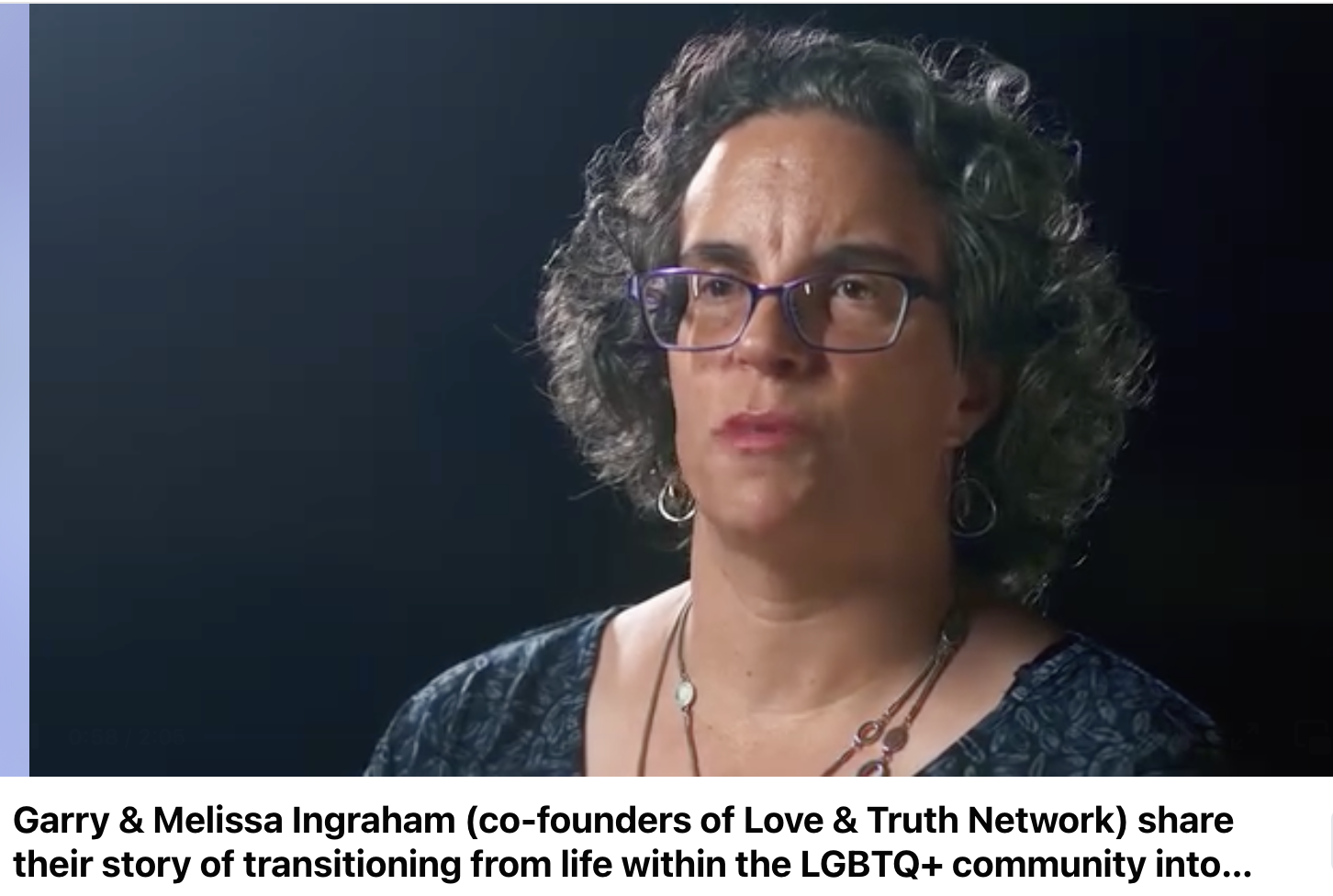

Hinson is not the only Arizona therapist with ties to Exodus International and the ex-gay movement. Melissa Ingraham, another licensed professional counselor in Arizona, was also listed on the Exodus website.

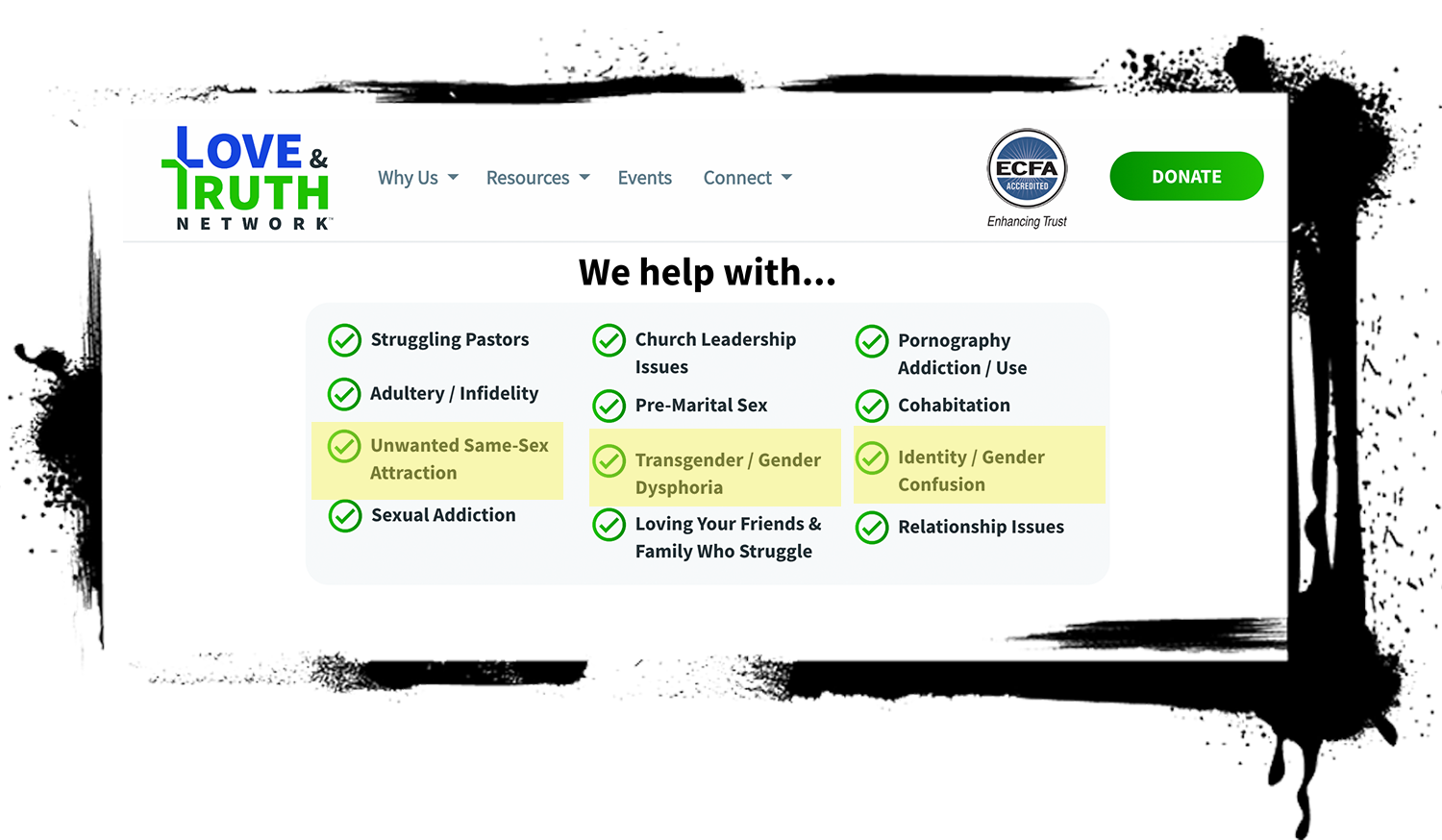

In 2013, Ingraham and her husband, Garry, formed the Arizona-based Love And Truth Network, which purports to help others on their journey to freedom from “sexual and relational brokenness (including homosexuality).” The ministry is listed on the directory of the Restored Hope Network, a group widely touted as the successor to Exodus International.

“Just because I felt something didn’t make it right,” Melissa Ingraham said in a Facebook video, referring to her attraction to other women. “Because that had been my entire justification for this lesbian relationship and believing that this was who I was supposed to be.”

Melissa Ingraham is listed separately on the Restored Hope Network as a “therapist affiliate” in Arizona. She is also listed on the conservative Focus on the Family’s Christian Counselor Network as specializing in “sexual and gender identity issues.”

Conversion therapy or reparative therapy isn’t explicitly mentioned by Ingraham on her practice’s website, Overflow Christian Counseling.

Melissa Ingraham did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

According to the Trevor Project, licensed conversion therapists have been less likely to openly advertise their services to the public in order to escape growing public disapproval of the practice.

In addition, the success stories conversion therapists had relied on are disappearing.

In 2013, Exodus International disbanded. Alan Chambers, the leader of the ministry, renounced the organization, making a public apology to the LGBTQ+ community. He is one of several prominent ex-gay spokespeople to come out as still being attracted to the same-sex. The co-founder of Brothers on a Road Less Traveled, Matheson, left the organization in 2019 and also came out as gay.

NARTH rebranded itself as the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity (ATCSI) in 2014. The organization began to distance itself from the term reparative therapy entirely, but still publishes on its website that it can help clients move away from “unwanted same-sex attraction.”

Now, conversion therapists and their advocates have mostly abandoned the term “reparative therapy” in favor of the monikers “Reintegrative Therapy” and “SAFE-T” (Sexual Attraction Fluidity Exploration in Therapy).

Carolyn Pela, former president of ATCSI, is a licensed marriage and family therapist in Arizona, practicing at Freedom Family Counseling in Glendale. She has a long history in the movement, having worked alongside Nicolosi, and she is the current vice chair of the International Foundation for Therapeutic and Counseling Choice (IFTCC), another pro-conversion therapy group.

She co-authored a study in an attempt to position Reintegrative Therapy and SAFE-T as separate from conversion therapy, while still being a practice that aimed to reduce clients’ same-sex attractions.

In an appearance on a conservative online show, she stated that she does not believe in sexual orientation, saying that doing so gives ground to queer people as even having sexual identities.

“Essentially, what’s being said is that you should privilege your sexual feelings over your core values of faith,” Pela said.

When asked by LOOKOUT whether a client suppressing their same-sex attraction was an acceptable outcome for her practice, Pela said she puts her clients’ goals first.

“Sexual fluidity is the norm,” she said. “Therapist demands, or even encouragement, for rigid compliance to categories of sexuality or sexual identities in order to support the cultural narrative, or someone else's political agenda is, in my view, unethical practice.”

Pela sent LOOKOUT the citations for two papers authored by psychologist Lisa Diamond, and recommended them as sources to learn more about sexual fluidity. Hinson also cited Diamond in his response to LOOKOUT, saying that "fluidity is common with regard to attraction."

Diamond, though, said her work was being used for disinformation.

“I am so tired of this,” Diamond said when reached for comment by LOOKOUT. “Fluidity has nothing even to do with it…It’s about the reasons that you even want to change.” Diamond said she is disheartened that conversion therapists have twisted her words to support the practice for close to a decade.

Diamond’s research, instead, explains that sexual attraction is complex and can change over time on its own.

“And that is fundamentally different from an attempt to sculpt or change or shape your sexuality in a particular direction,” she said.

“It is fluidity plus shame that is harmful,” she continued. “Shame is the problem, and shame doesn't come from individuals — it comes from our culture, and it comes from religion, and it comes from a therapist saying, ‘Why don't you try a little bit harder?’”

Adames felt ashamed enough to entertain going to Journey Into Manhood. He was about to go, having paid the security deposit, when his roommate told him he didn’t need to.

“There’s nothing wrong with you,” Adames remembers his roommate saying.

So he pulled out of the camp and eventually stopped going to his conversion therapy sessions.

“[He was] one voice of reason out of, like, all the other church people I was around,” Adames recalled. “And he’s still my best friend.”

Over the years, Adames has reconciled his faith with his sexuality. And he has moved from being counseled to now counseling others: He works as a pastoral counselor at a church that accepts him for who he is:

“There have been Christians that have not had an issue with it for decades,” he said.

Adames specializes in working with clients who have experienced conversion therapy or who have grown up in disaffirming households.

“If they’re not able to have that support in their current life, what does that look like?” he asked. For some, that might mean leaving the church entirely, but Adames doesn’t judge. “Some people do have to leave the faith in order to get better.”

If you like independent and accountability-driven queer news, then you'll love LOOKOUT's weekly newsletter.

LOOKOUT Publications is a federally recognized nonprofit news outlet. EIN Number:92-3129757